Dying for Splendour

An Autobiographic Playlist

—David Keenan

—David Keenan

A: “The hazy nature of memory lends itself well to a certain kind of introspection. Remembering tends to imbue the referents of our experiences with an imagined, unlifelikeness that says more about us than it does it.”

B: “Hmm…but then what of the quarter-million madeds at Knebworth in 1996 singing every word back at Liam and Noel? Surely the internal re-presencing of such events has as much to do with, in this case, Slide Away and Don’t Look Back in Anger, as it does the individual doing the remembering?”

AB: “Who knows (cares), perhaps we ought not think about it now. Instead, let us read on about some of the wonderful referents that David Keenan thinks – at risk of putting words in his mouth (by putting words in his mouth) – the world would be worse off without/is better off with.”

Liner Notes

Portishead, Third

Island

If the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band hadda growed up on the west coast of the UK in the 1970s, with a vision of Europe-as-cosmos, with Berlin as the future and the Iron Curtain as The Milky Way, with Nico as a constellation – The Two Daughters, let’s call it – with Wire as a satellite, in other words Dome as a companion, with Joe Meek instead of Kim Fowley (both figures representing the most intuitive exploitation producers of their respective continents) as a ‘guiding light’, then Third (it evens sounds like a WCPAEB title) may well have been their Vol. 3. “The Rip” is in the same tradition of hallucinatory pop half in love with easeful death as The Chills’ “Pink Frost” and A.C. Marias’ “One Of Our Girls (Has Gone Missing)” and builds to a classic riff-as-chorus moment that feels like the mind-blotting surrender to the current that the song has been intimating all along. Portishead’s first album, released in 1994, chimed with the time in which it was made so that now it sounds very period specific and dated but this album was not what anyone wanted to hear from them in 2008, dystopian sci-fi motorik with a paranoiac drone rock edge, so that it looks to remain incapable of speaking for a certain historical/cultural moment for the rest of its conceivable shelf-life.

King Crimson, Ladies Of The Road

Discipline Global Mobile

Last night I had a dream that I discovered a massive King Crimson box set in my archive that came with a beat up guitar – I was disappointed that it wasn’t a bass guitar, that would definitely be my choice of instrument in Crimson, although normally bass guitar seems like the most boring instrument in the world – alongside things like replica tour passes and memorabilia and a huge book called First Steps Towards An Understanding Of Songcraft. It made partial sense; is there any other group so focussed on the mechanics of playing in a band, the dysfunctional, interpersonal relationships, the obsessive documenting of specific line-ups, the dialectic between improvisation and structure? But like The Grateful Dead, perhaps the only other group you could really say that about, Crimson’s songcraft is fairly perfunctory, the vocals are often poor (though I dig them, still) and the bulk of the tracks exist simply as jumping off points for the jam, which explains the existence of all of the endlessly amazing live sets. The second disc on Ladies Of The Road represents a dream Crimson edit, all the ‘guitar smashing bits’ – the saxophone and guitar solos – from 1971-72 takes of “21st Century Schizoid Man” run together. The first disc is also great, with a mix of live material from the same line-up with weak vocals that are perversely appealing in their earnestness and lyrics in a kind of brainy undergraduate sword and sorcery style that make me feel nostalgic for my 12 year old self. But for me Crimson is all about ball-busting bottom end, or at least how it interacts with Fripp’s guitar, and here Boz Burrell, an almost archetypal name for a hairy UK rocker in the early 1970s, is on tectonic form.

John Coltrane, Sun Ship

Impulse

I often dream of the sun as a transport or a ship but mostly I dream of it as being horse drawn, with four dark mares leading it on reigns across the sky. But in this case it feels as if Coltrane is talking about the body as the ship of the sun, the transport of solar energy into and through incarnation and its expression in sound and thought. This is a signal Coltrane recording for several reasons and a long-term personal favourite and it sounds great on my new speakers. It’s one of the few, if not the only (?) late period ‘classic quartet’ session not engineered by Rudy Van Gelder in New Jersey, recorded instead at RCA Victor in NYC in the summer of 1965. Plus it’s the second from last studio session that Coltrane would ever cut with pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones. A lot of intense noise music tends towards a contrary feel of stillness, a form of overloaded gridlock that can actually be quite meditative and this recording captures that feeling perfectly, not that it’s particularly noisy, but it’s emotionally tumultuous with a feeling of untouchable serenity in its depths. The change of recording venue somehow punks the sound a little and Jones is on particularly pugilistic form, matching bassist Jimmy Garrison’s high-minded refusal to get down with cuffs, checks and counterblows. Coltrane is playing with that same heavenly fire coursing through his veins and as much as I love the late period recordings with Pharaoh, Rashied and Alice this is a tantalising glimpse of how things might have developed had a group that had worked together so intensely and telepathically for three solid years taken that final leap together. As it is Sun Ship represents a dense singularity in the Coltrane discography.

Omit, Interceptor

Helen Scarsdale Agency

There are two exemplary translators of the landscape of New Zealand into sound, specifically the endlessly epic beauty of the South Island, two artists whose music sounds like a particular reflection of their environs: Roy Montgomery, whose most overt visioning of landscape are 1995’s Scenes From The South Island and 2007’s ‘companion’ volume, Inroads: New And Collected Works (with its ‘Paved’ and ‘Unpaved’ discs a knowing nod to travellers in NZ’s wilderness) and Clinton Williams aka Omit. But whereas Montgomery’s music is all about figures in a landscape – his reading of The Velvet Underground’s “Ocean” is particularly informative, a solitary witness to the waves crashing against the shore – Omit’s music is the sound of the landscape itself, unpopulated, lonely, beautifully austere. Williams comes from Blenheim, which is a great place to drink small batch NZ craft beer and a dot on the never-ending planes and alpine peaks of the surrounding countryside. 2008’s Interceptor is his masterpiece, somehow less obviously repetitive than earlier works while still feeding only on itself, with pulses crawling through endless handmade circuit boards and analogue sculptures as if they are marking aeonic time and tracks based around nothing but the occult tick tick tick of zeros and ones, as if he is sounding the mathematics of elemental construction, the tectonics of place. Tonight I played this one back to back with Monoton aka Konrad Becker’s singular 1982 recording, Monotonprodukt07, and now I know how Moses felt in the basket.

Lon Milo Duquette, I’m Baba Lon

Ninety Three Records

It’s said that when the Buddhist master and crazy wisdom teacher Chögyam Trungpa would give lectures to his students, often raving drunk or out of his head on cocaine, perched on the edge of the stage with his legs dangling down, whether at the Naropa Institute that he founded in Boulder, Colorado, where he invited people like Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs to teach courses or at Kagyu Samye Ling, the first Tibetan centre in the West, co-founded by Trungpa in the Scottish Borders, the lectures weren’t about the dharma so much as they were the dharma itself.

Lon Milo Duquette, as far as I know, is a high-ranking member of Aleister Crowley’s reformed Ordo Templi Orientis or O.T.O. and I’m Baba Lon presents a series of studio recordings, mostly with Lon on acoustic guitar and vocals, that are not so much about the dharma as the dharma itself. I first encountered Lon when he gave a talk at a crystal healing store (!) in Glasgow and when I heard he was playing music a few nights later at a bar in the centre of town I had been sufficiently impressed to at least make the effort to check him out. He caught me off guard and by the end of the night I was reduced to tears. Indeed, I don’t think I have ever been the same since. Most contemporary occultist’s music taste seems to run towards cheesy Goth or Industrial music but Lon comes out of the world of Gershwin and the laidback folk stylings of Michael Hurley and there’s a sepia-tinged nostalgia to his music that reminds me of Robert Crumb’s vision of early 20th century America, back when “everybody wore hats”. I’m Baba Lon might not have quite the contact high of seeing Lon perform live but it’s haiku sharp and his vision of all-encompassing love as change and change as the universe’s perpetual longing for unity in “Love’s Song” has made my day complete on many, many occasions and his evocation of the night his father danced a solitary dance with Jean Harlow is the greatest metaphor-in-song for the endless coming-on of reality that I’ve ever heard laid down, and laid down solid!, on six steel strings.

MFH 1979-85

Forced Nostalgia

The first wave of Industrial music in the UK, from the late 70s to the early 80s, was the equivalent of the mid-60s garage band explosion in the USA. It was made by disaffected teens with little-to-nada in terms of instrumental ability, power-crying over hormones-as-chaos, jamming two chord (or more properly two note) paeans to teenage alienation in the face of imminent nuclear annihilation or death by rabies or hallucinatory hypothermia or name your goddamn disease. For anyone growing up in the 1970s in the UK it is possible to have a nostalgia for a permanent state of siege. If punk was all about a nostalgia for the future, or so they say, then the Industrial music of the UK (and maybe of San Francisco, positioned as it was right at the end of the land/end of the world and where both the Sex Pistols and Throbbing Gristle ultimately came to implode, I’m thinking of Factrix, Minimal Man, Monte Cazazza et al…) was more about a homesickness for apocalypse. The various cassette releases by MFH, the duo of Andrew Cox and David Elliott, best articulate this goofy, dramatic aesthetic, scientific geeks under the spell of night-time, backwards jamming “Louie Louie” on homemade circuitry. Most of the tracks gathered here, culled from releases on their own YHR imprint that also put out stuff by Cluster, Conrad Schnitzler, Maurizio Bianchi and Asmus Tietchens amongst others, are simple mono-rhythms left to run, spelling out occult chemistry experiments and animating paranoid teenage Frankensteins with alla the puberty wrongs of the best of The Cramps. But still it’s spellbinding. This is the soundtrack to the power cuts of 1974/75, which are some of my earliest memories, and that bred in me a childhood love of the dark and of its many consolations. David Elliott went on to write about a lot of great experimental music for Sounds, the only one of the UK music weeklies that I never wrote for but the one I would have liked to the most.

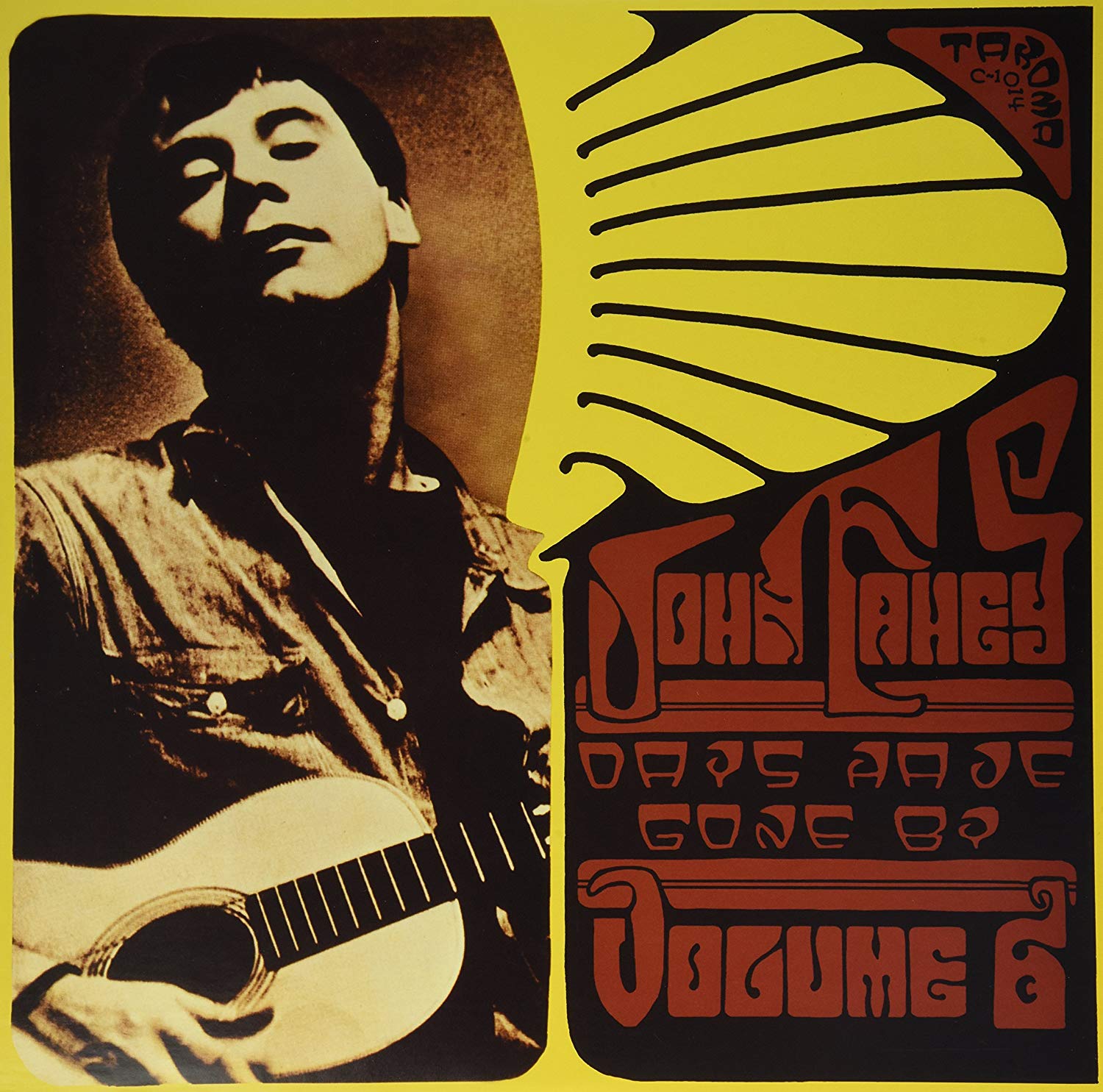

John Fahey, Days Have Gone By

Takoma

There is a photograph that exists somewhere, though I have never seen it and so am forced to imagine it, of myself with John Fahey and, I think, three other people, though there could be more. It was taken during Fahey’s last tour of the UK in the Queens Hall in Edinburgh. That night I was being pursued by a girl who Fahey was pursuing himself. Pictured, from left to right, in my mind, there’s Brian Hogg, publisher of the Bam Balam fanzine from the mid-70s, who looks as if he may have American Indian in his family, Simon Black, who owned every copy of the NME from the beginning up until it became completely uninteresting, which I’m guessing was some time in the 1990s, and who launched and managed the record department of John Smith’s book store in Byres Road in Glasgow where both Brian and I worked in the late 1990s, then there’s Fahey himself, who is larger and rounder than any of us, he has us in a bear hug, almost, and who is wearing pointy wraparound shades and whose belly is exposed, then there’s me, the youngest member of the group, squinting towards the camera, simultaneously awkward and awed, very much aware of myself as a representative of the next generation, and next to me the late Stuart Cruickshank, a producer for BBC Scotland, specifically Beat Patrol, which was once known as Rock On Scotland and whose intro music was “Do You Remember Rock N Roll Radio?” by The Ramones. In my mind I see us walking away from the photograph in different directions all except for Fahey who stands there for a little while longer, right in the middle of the shot.

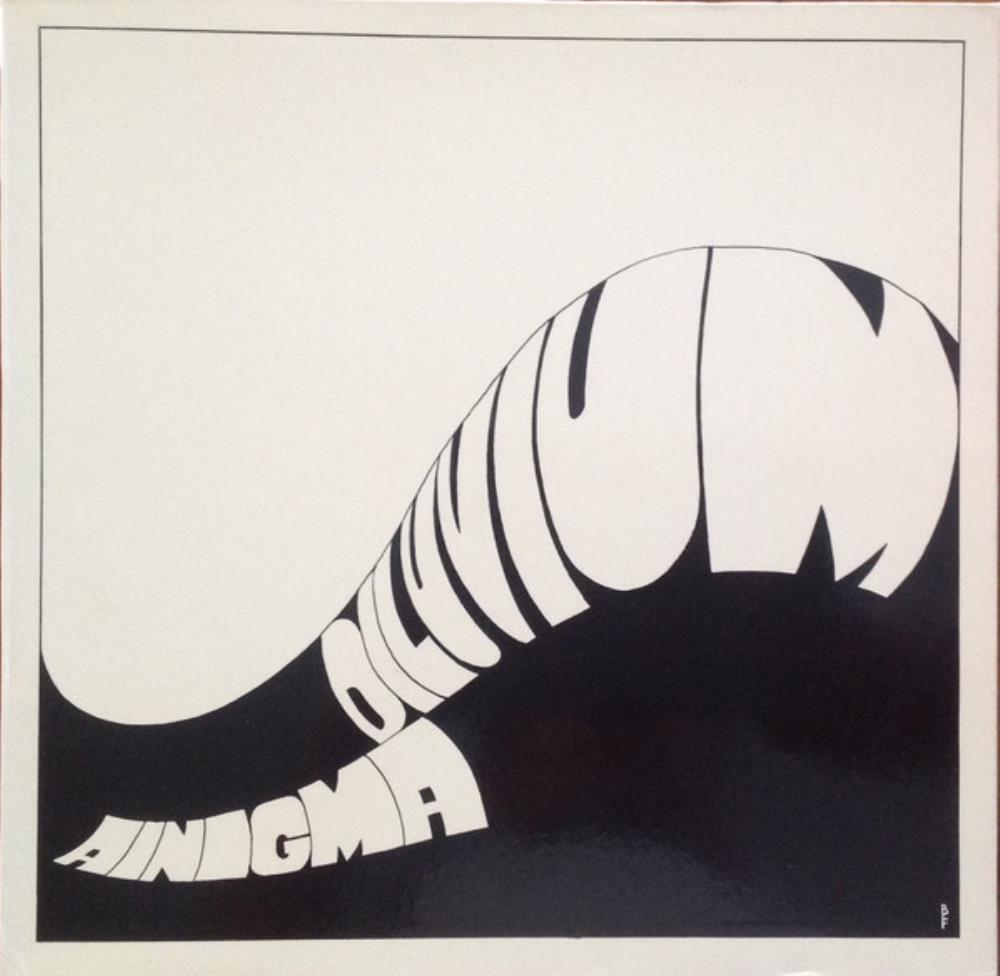

Ainigma, Diluvium

Little Wing

“Your whole life is a race/for things that are gonna end anyway/you can’t keep on running”. I used to love stupidity and energy and excess and young people acting tough and making big statements and dressing to kill and mouthing off. Then I hated them, I hated young people, hated their bullshit, their clichés, their outfits, their stupidity. Now I love them all over again. It’s like that whole period that Buddhists talk about where mountains are no longer mountains. I’ve pushed passed that, back to where young people are just young people. And I’m enjoying them all over again. The thing I hated most about punk was its emphasis on boredom. That seems like the exact opposite of the original punk impulse. What’s that cartoon, that detourned Jamie Reid thing where some character is complaining about how ‘they’ won’t do anything to raise the standard of boredom? Wasn’t that the whole point? To raise it yourself, to find an interest, to create something, not to sit around and wait for someone else to entertain you? Ainigma’s private press LP pre-dates punk by a few years. They were around in Germany between 1972 and 74. The guitarist and drummer were only 15 years old. All of their lyrics are about how time is running out and all things are fading. At fifteen years old! Yet they cared enough to press this amazing LP in the face of universal entropy. The drummer is ridiculous. Every break is a bombastic thug-punk solo while gothic keyboards and the crunchiest fuzz this side of Crushed Butler squeeze every nuance of electricity from the vocalists’ pronouncements of teenage Gnostic endings. When I grew up in Airdrie we had a mystical punk who everyone called Street Hassle who would come out with the same kind of gnomic gems while standing in the gutter drinking a can of Special Brew with a cut-off t-shirt in the freezing cold. I later heard he ended up in jail. All of the punks in Airdrie ended up in jail, either that or dead through drugs and drink or working as social workers. I don’t know which is worse.

Bill Comeau Gentle Revolution

Avant Garde

Favourite sleeve bar-none except for maybe A To Austr’s Musics From Holyground: it’s a teen hang-out by a lake and no one is smoking or cracking a brew or causing havoc or dunking each other in the water, even though 75% of the guys are hanging around topless within a few feet of sexy librarian earth mother hots with wet bikini bottoms and kaftans. All except for Bill, that is, at least I’m guessing it’s Bill, otherwise this guy was framed by him, because the focus is on one guy in particular as the cover star, hovering just behind the conversation, standing there with an early underpants reveal that is total ghetto Christian style while he attempts to lean pensively on one finger with no elbow support, which is a tough deal, but which may also be a Christian way of secretly flipping the bird to the camera, you know, like using the wrong finger the way you would substitute the word ‘sugar’ for ‘shit’. No punishment for that. But the last thing I want to do is pick on Bill, if it even is him, because Bill is the paradigm for good guy cool. I imagine that the woman in front of him is his partner, and that maybe she’s pregnant (looks like it a little)? And that his demand for a Gentle Revolution is as much for the good of the next generation as it is for the kids at the swimming hole. Avant Garde was one of the great Christian folk/rock/psych labels and although there are more overtly ‘weird’ LPs on the label, Crosscurrent Community’s Let The Cosmos Ring even gave its name to a Tower Recordings off-shoot, Gentle Revolution has an atmosphere of goofy, heartfelt reverie that is more truly ‘counter-cultural’ than any third-eye sqouzing private. Plus it features my all-time favourite Beatles cover, or rather my only favourite Beatles cover, in the form of Bill’s impassioned take on “Eleanor Rigby”.

Fushitsusha, Pathetique

PSF

I don’t know what I want on my gravestone, but I know that I want one. I covet a secret memorial in an out of the way cemetery in a wet valley at the end of a single track road, a final wild mooring, in the same way that I covet weirdo one off records and self-published books on transformational magic. Right now I think I want it to read ‘The Astonished Man’. List the cause of death as a surfeit of ecstasy. Play the first track from Fushitsusha’s Pathetique at my funeral. Then let me go.

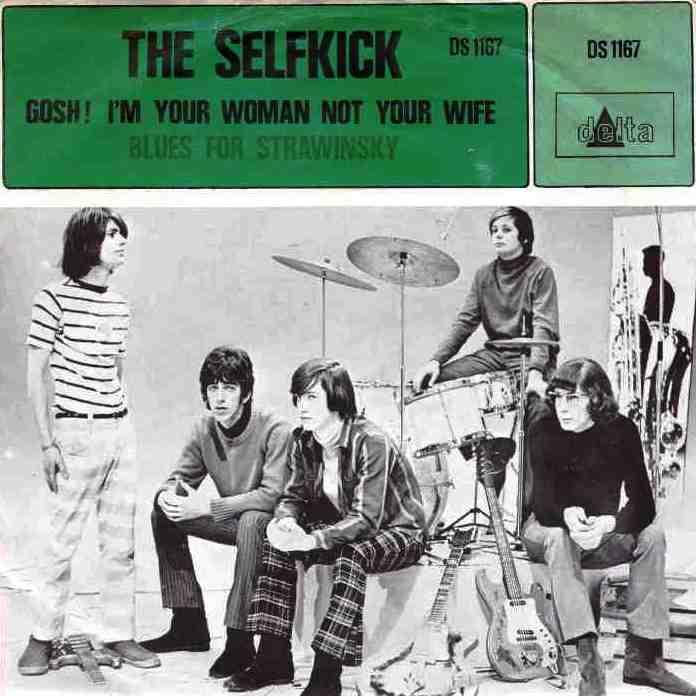

The Selfkick, Gosh! I’m Your Woman Not Your Wife/Blues For Strawinsky

Delta

I used to know this guy who was a teenage poet and comic artist and moody self-publisher who had a flat at the legendary Red Road Flats in Glasgow where one night I actually saw someone throw a TV out of a window, just like in a rockumentary, only more real and he wasn’t made to pay for it afterwards. Anyway, we started doing this club night together, we thought we were the two most Sixtiest guys on the scene, in fact years later he used that exact description as a chat-up line – that worked – in a club in London after we briefly renewed our friendship and when he was two-timing this beautiful young girl who was half Swedish and half Japanese and there was an inevitable split, I can’t remember how, he was a motherless son, that’s how he described himself, all the poets are motherless sons, he said, and so he was super-touchy and domineering and controlling and moody in a way that was attractive but ultimately incompatible with my own early 20s determination to come out on top. He started dating my sister, and writing poems about her, and he began self-publishing, leaving Xeroxed and stapled poetry collections in the old Third Eye Centre on Sauchiehall Street. His favourite album was Harvest by Neil Young and his favourite paperback, he was never without it, was Kafka’s Diaries. Eventually he moved to Edinburgh where he started up his own short-lived Sixties night called The Dandelion Clock. On the poster he listed all of these obscure beat, psych and freakbeat groups that alla my friends – who considered themselves experts on the scene, one guy was even trying to collect every 7 inch released in 1967 – doubted even existed. Top of the list in terms of carburettor dung was The Selfkick. But they did exist, and he played this still-amazing single at the inaugural night of the club, a wild Dutch R ‘n’ B side that outdid even Q65 and The Outsiders in terms of taking rock at its word and being ahead of the game, with one of the wildest harmonica breaks of all time and lyrics that trump even Rodd Keith in terms of re-gendered surrealism. But then he sat on the generator and it fused and the night came to a desultory end and someone broke in through a skylight in the middle of the night and stole the PA he had hired, which luckily was recovered the next day stashed down a close in the old town. The last time I heard from him he called to invite me to a Mod night in a club in Soho, left a message on my answer machine, this is when I was living in Clapton, in North London, in another life altogether. But I never returned his call.

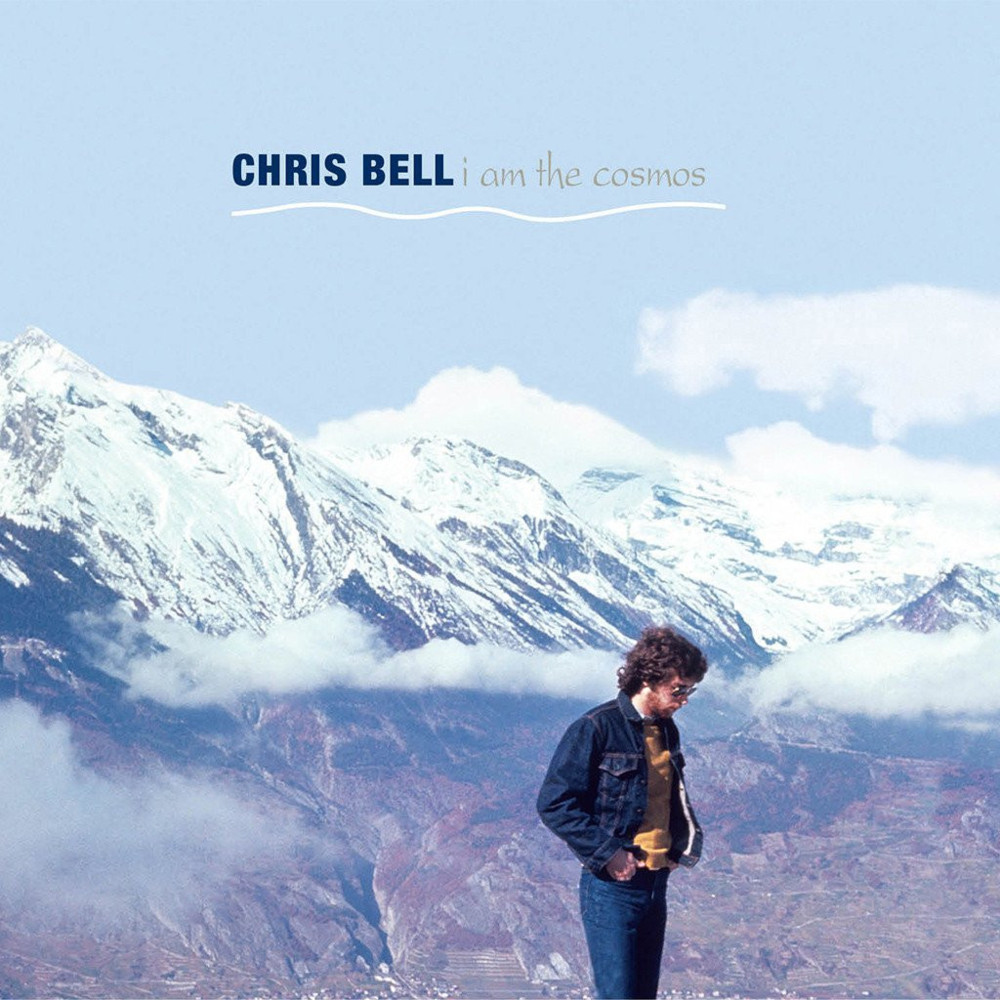

Chris Bell, I Am The Cosmos

Rykodisc

In many ways the ultimate bedsitter harsh misery record, right from the cover shot that friends would delight in telling you was taken at the top of the Himalayas or something like that on a trip that Bell’s brother had arranged in order to try to head-off the depression that was slowly shutting him down, to no avail, obviously, he’s looking down at the ground, he has his hands in his pockets, I think, even while he exhorts himself in the lyrics to “look up, look up, you’ll see the sky”, then there’s the jaw-dropping “Speed Of Sound” where Bell jump-cuts from the story of a breakup to the vision of a plane crashing with a dead pilot at the helm: “Plane goes down/it will not land/the pilot’s dead/no one in command”. I’ve heard the last line should really be “nowhere to be found” but the pilot is dead, his body is slumped over the controls, he hasn’t yet hit the ground, its only afterwards that he’ll leave no trace, which makes it all the more harrowing, indeed the only comparable moment in rock/roll performance I can think of, when something turns from a personal confession of hurt to a biblical vision of pure existential terror, is on The Flying Burrito Brothers’ “$1000 Wedding”, from their debut LP, The Gilded Palace Of Sin, where Gram Parsons combines the vision of a young girl cut down on the day of her wedding with the image of “the fiercest beast” being put to sleep “the same silly way” in a way that comes over like an atavistic mishearing.

The Vaseline, Dying For It

53rd & 3rd

This has to be modelled on Redd Kross’s amazing 1984 re-think of their hands-down greatest track, “Linda Blair”, which appeared on their always notoriously tough to score ‘covers’ record Teen Babes From Monsanto. From their early obsession with scuzzy LA nightlife and underbelly glitz – Valley Of The Dolls via the Sharon Tate murders – through their re-invention as a kind of goodtime waxwork glam, Redd Kross were one of the first groups to marry two-chord caveman ugh with endless wipeout guitar solos, an aesthetic of excess in restraint, or restraint in excess, that somehow spoke to Glasgow of 1987. This was round about the time when The Pastels were using photocopied pictures of Frankie Howard on their posters with tag lines like “Up Your Arse Missus, It’s The Pastels and The Vaselines” in an attempt to distance themselves from the sexless anoraking they were being lumped in with by the music press using nothing but smut and celebratory aesthetics. Played alongside The Pastels’ “Sit On It Mother” and the Pastel-curated Good Feeling compilation (where Redd Kross put in an appearance with “Blow You A Kiss In The Wind” from the Teen Babes… LP) the Pastel-produced Dying For It EP remains an object lesson in minimal amp-humping maximalism, with a breakout guitar solo that just leers all over the vinyl. In terms of glam The Vaselines were always more Divine than Motley Crue, which demonstrates the kind of creative acumen that would have saved Redd Kross a whole lot of dud vinyl throughout their twilight years.

Iggy Pop & James Williamson, Kill City

Bomp

This was the soundtrack to my first teenage trip to London, I was in town round about the same time that Matthew Valentine was living there and we both wonder if we were at the same gig by Blyth Power in Finsbury Park. Who knows? I remember one night Janice Long, on her Radio One show that was kinda John Peel Jr, played “Heartbeat” by The Psychedelic Furs and said it was the song she always played while she was getting ready to go out and somehow that weird sleazy saxophone sound became imprinted in my mind, like Pavlov’s Goth, as shorthand for lurid teenage urban night-time. Before I go out for the night these days I play Kill City. For pure decadent anything-could-happen destructo sex and sleaze appeal it stands tall alongside the second Suicide album. I bought it on that first trip to London when a pal and I made our first ever drug deal in the public toilets (now closed) outside the Rough Trade shop in Talbot Road, when some magical derelict offered us a handful of prime bud that we shared with him in the park across the way. Then we sat on the kerb outside Rough Trade for about an hour and a half before heading to the Blyth Power gig. Then we went back to the hotel that we were sharing with my mum. When I got home to Airdrie I played “I Got Nothing” and “Johanna” and “Night Theme” and felt like a true subterranean.

Felt, The Splendour Of Fear

Cherry Red

I once spent the best part of three days in a row hanging out with Lawrence from Felt in a record shop in Glasgow. We talked about The Kinks, Annette Peacock and his first ever gigs, which were T Rex and Roxy Music, and how he was just a kid but he befriended two beautiful girls in the queue that had long scarves on and endless hair and who asked him if he was going to the Mott The Hoople show the next week. Later that night he lost them in the crowd but he said that he still thinks about them to this day. He told me he had bumped into the singer of a famous Glasgow indie band just outside the shop who didn’t even know there was a record shop there. He looks like a downloader, he said to me, and he shook his head. It was the worst insult he could think of. Lawrence told me that he was a words man, that it was all about words, yet what seemed to attract him in terms of the records that he would pull out of the bins was the design of the sleeve. His appreciation was primarily, initially, visual.

The music of Felt came back to me later in life the way the visions of the girls at his first concert came back to Lawrence. The music on The Splendour Of Fear is mostly instrumental, endless arpeggios riding straight into the sun. It makes me think of hospitals or childhood or illness or old age, in the way that the music seems trapped, it speaks of something happening somewhere else, always just out of reach, beyond articulation, or something that’s happened already or will happen in the future. I see myself in a bed, at night, with a set of headphones on, and I’m remembering, or getting ready to forget, or something like that.

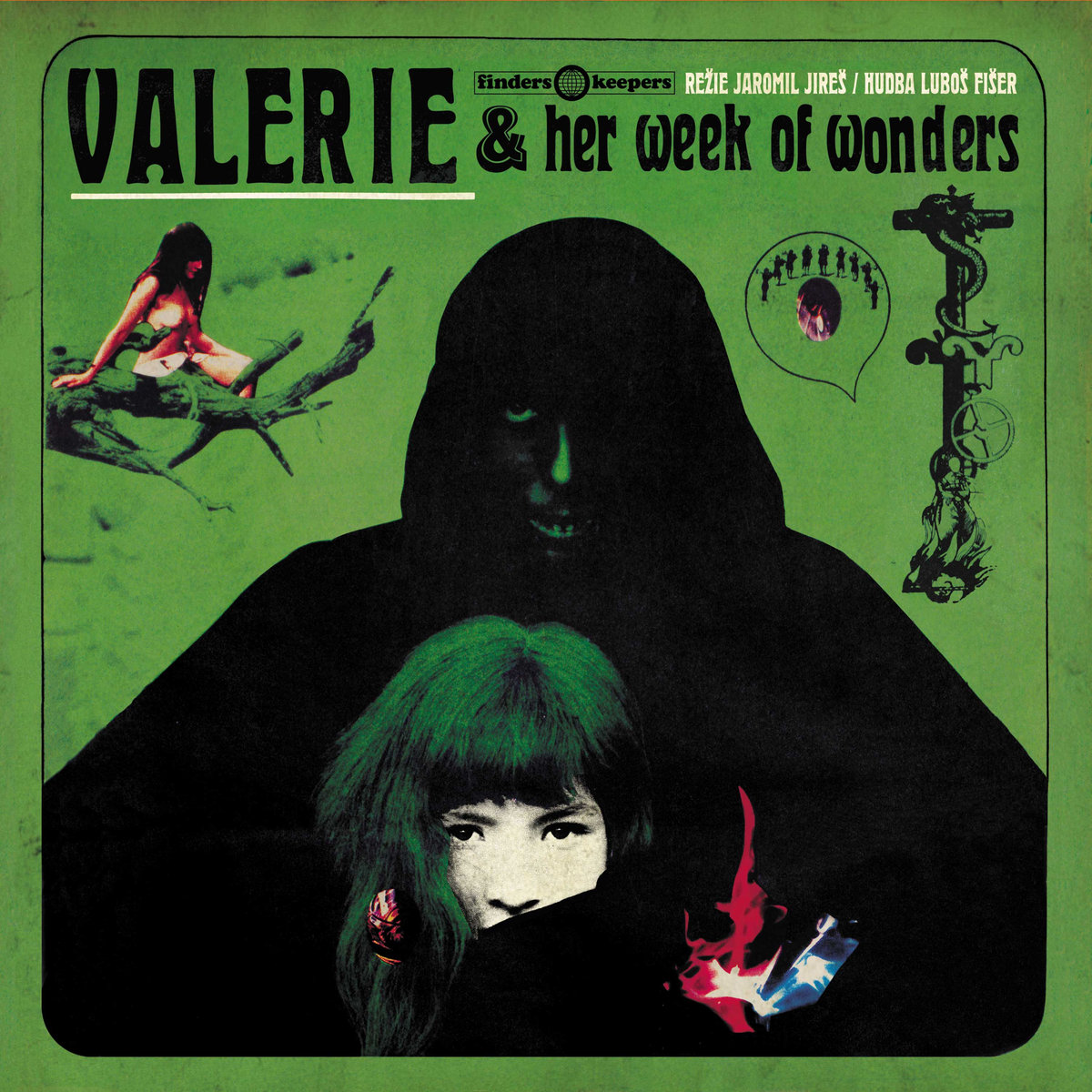

Lubos Fiser, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

Finders Keepers

I hated soundtracks for so long. I thought that listening to them was some kind of cop-out, like it was more about wallpaper or some kind of halfway point, like if it hadn’t been conceived purely as music minus image it was somehow compromised, cause I barely watch movies except for horror or Euro sleaze or Eric Rohmer and I don’t have a TV and I didn’t want anything to do with it if it wasn’t music or books. There was a glut of reissues in the 1990s on LP when I was working in a record shop in Glasgow but no matter how much I loved Bruno Nicolai when I was watching a Jess Franco movie I somehow couldn’t imagine sitting down to listen to it outside of that experience. That is until I heard Lubos Fiser’s soundtrack to Valerie. I think Valerie and its soundtrack are more truly, deeply magical than anything by Kenneth Anger and Mick Jagger and Bobby Beausoleil. I think real magic is celebratory, light, forgiving, gentle, secret, invisible, weightless. I don’t think broody goatees in flowing capes makes for magic. True magicians have mastered invisibility. That’s a basic requisite. So with this soundtrack, where we have the initiation of a little girl into life and death via music that is as celebratory as the change of the seasons. The main motif seems to somehow reconcile nostalgia, hope, remembrance, bravery, fun, sadness, humour, lust and longing in a way that has little parallel and that makes it more truly magical, and more truly radical, than anything that might more overtly stand for both.

Biography

Award-winning Author/Volcanic Tounge, 2004–2015