Looking for an Exit:

Sonic Coordinates for Egress

—Matt Colquhoun

Sonic Coordinates for Egress

—Matt Colquhoun

In the introduction to his unfinished book, Acid Communism, the late Mark Fisher — famous for his love of post-punk, jungle, and a range of contemporary pop-experimentalists — surprised friends and fans alike by writing positively about the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s.

Fisher had previously declared, on his k-punk blog, that “hippie was fundamentally a middle class male phenomenon” defined by a “hedonic infantilism”. For him, the hippie’s characteristic sloppiness, “ill-fitting clothes, unkempt appearance and Fuzzed-out psychedelic fascist drug talk displayed a disdain for sensuality”. For Mark Fisher, ever the ardent Spinozist, there was no greater crime. The point, he writes elsewhere, is not to get off your head but “to get out through your head … auto-effect[ing] your brain into a state of ecstasy.” As fun as they may be for some, in the grand scheme of things, the drugs simply don’t work.

“When hippies rose from their supine hedono-haze to assume power,” he continues, “they brought their contempt for sensuality with them.” Culturally speaking, the shadow of this moment is long. With the new sensuality of post-punk defeated, Fisher connects the virulence of this “anti-sensual sensibility” to the cultural yuppies of the 1990s, epitomised by the Young British Artists and the “laddishness” of Britpop. It is hard to deny the prevalence of the counterculture’s negative trajectory when framed in this way. Although, at first, it seems like there is little more than a similar taste in sunglasses to connect the Beatles and Oasis, for instance, the cul-de-sac of — as Fisher puts it — “hey man, it’s all about the mind!” was as much the driving force behind the “bleary, blurry, beery, leery, lairy” vibe of Britpop as it was the fevered popularity of LSD.

Despite this unflattering appraisal from the mid-2000s, it seemed that Fisher later softened his opinion on the counterculture as a whole. He had begun to appreciate the political potentials of its best cultural offerings. These were not to be found in the surrealist abstractions of an acid test, however, but in the cultural artefacts that built new bridges between class consciousness and psychedelic consciousness. For instance, in the introduction to Acid Communism, Fisher champions the Kinks’ “Sunny Afternoon” and the Beatles’ “I’m Only Sleeping” as two tracks, both released in 1966, that were able to apprehend “the anxiety-dream toil of everyday life from a perspective that floated alongside, above or beyond it: whether it was the busy street glimpsed from the high window of a late sleeper, whose bed becomes a gently idling rowing boat; the fog and frost of a Monday morning abjured from a sunny Sunday afternoon that does not need to end; or the urgencies of business airily disdained from the eyrie of a meandering aristocratic pile, now occupied by working-class dreamers who will never clock on again.”

However, there was more to Fisher’s last political provocation than the average BBC Radio 4 listener’s dream of a quiet Sunday that never ends. More generally, he was interested — and had always been interested — in the ways that radical political messages could be smuggled into the collective consciousness through popular culture. He was also intrigued by the ways that pop culture could not only entice us with its infectious euphoria but also push past capitalism’s cooption of the pleasure principle into something deeper, something altogether unconscious, and bring it kicking and screaming to the surface.

This is a view of psychedelia that still needs to be affirmed. It is its function, in this sense, rather than its form, that remains relevant to us today: the way it connotes the manifestation of what is deep within the mind, not simply on its surface. Capitalism is very good at this too, but it cannot be allowed to hold the monopoly on our desires. There are alternatives and they are waiting to be excavated.

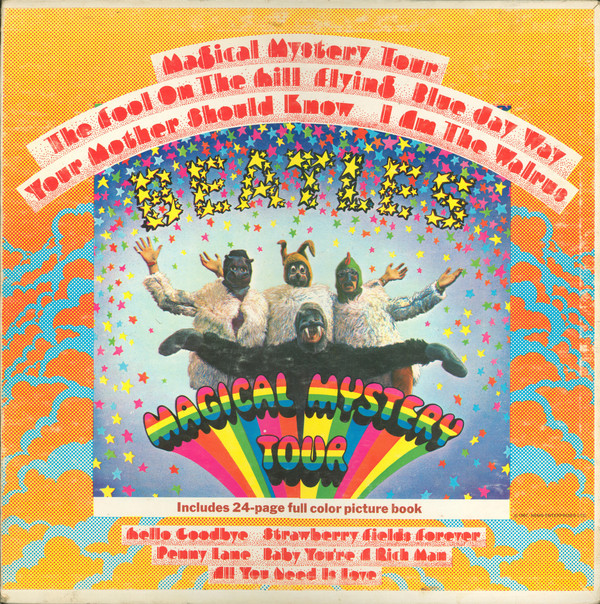

The Beatles

'Blue Jay Way'

As I put this playlist together, now under a government-sanctioned coronavirus lockdown in South London, I have found myself revisiting my Dad’s old Beatles records. They are a band that is, in many ways, synonymous with inward disappearances, both pop culturally and personally.

My Dad has often repeated the story that he first heard the Beatles in 1963, tucked up in bed with measles. His mother came home one day with the band’s EP from that year, The Beatles’ Hits, to cheer him up. The euphoria of that moment — receiving what was, at that time, such an enormous treat — stayed with him.

Under our current circumstances, it has also been hard not to think of the band’s collective ingress in 1966. Famously fed up with their own inaudibility during their live shows, due to the hysteria of their fanbase, they vowed to never play live again and instead immersed themselves in the capabilities of the recording studio.

Fisher’s comments regarding “I’m Only Sleeping” — taken from Revolver, their last album recorded before they left the world’s stages — could be read as a sign of things to come but, unfortunately, history has taken a different view of their output from this period. Whilst many continue to view the maximalist studio explosion of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the first product of those “studio years”, as a revolutionary moment for pop, its legacy has waned in the minds of many a more politically conscious critic. It’s effervescence died with the counterculture, they say. Others argue it was made almost immediately redundant by the socio-political upheavals in Europe the following year, in 1968. By all accounts, the band had reneged on their capacity to create a psychedelic class consciousness, and John Lennon’s solo attempts to the contrary still leave much to be desired, but perhaps the truth of the band’s legacy is somewhere in between the best and worst of its consequences.

These albums contain, on the one hand, the fantastical vibrancy of self-exploration, during which time the limits of a four-piece pop band were radically exceeded. On the other hand, on their 1967 albums most explicitly, the band also seems impotent, trapped by a phantastical melancholy, through which they live out the dream-like existence of a live band that is actually listened to. Just as Sgt. Pepper’s begins with vaudeville introductions and recorded crowd noise, the follow-up from the same year, Magical Mystery Tour, longs for the tour bus existence, instead settling for a tie-dye coach tour of the mind.

A song like “Blue Jay Way”, however, seems to emerge from somewhere else. The song’s origins are disappointingly mundane — it was apparently penned by a jetlagged George Harrison whilst waiting for his publicist to arrive at an LA mansion, nestled amongst the Hollywood Hills — but it also manages to capture the psychological landscape of showbiz ennui. To this day, it remains a strikingly hauntological siren song, made about a fictional city at a moment of creative conjuncture. It is a sonic go-between, bridging the gap between Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard and David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, appearing at an almost perfect midpoint between the two films, both synonymous with the rotten psychedelic-nostalgia of tinsel town and its Golden Age. Here Hollywood escapism is transformed into an ingrown problem, pushing through itself to perforate the thin skin of pop culture and reveal a grotesque new that is waiting underneath.

Unaware of its back story, the sounds of the song’s Hammond organ had a strange effect on me during my childhood. Devoid of cultural or historical context, much of the artwork of that time appeared nightmarish to me and it was only “Blue Jay Way” that seemed to acknowledge the darkened underbelly of decaying countercultural dreams. It was a song speaking to something else, reaching through its banal origins to some acknowledge the diffuse horror of inner / inside experience. By letting the outside in, it reaches new depths, below the superficial technicolour of the original acid moment and outside further still, beyond the pleasure principle that would ironically be the death of a wider movement.

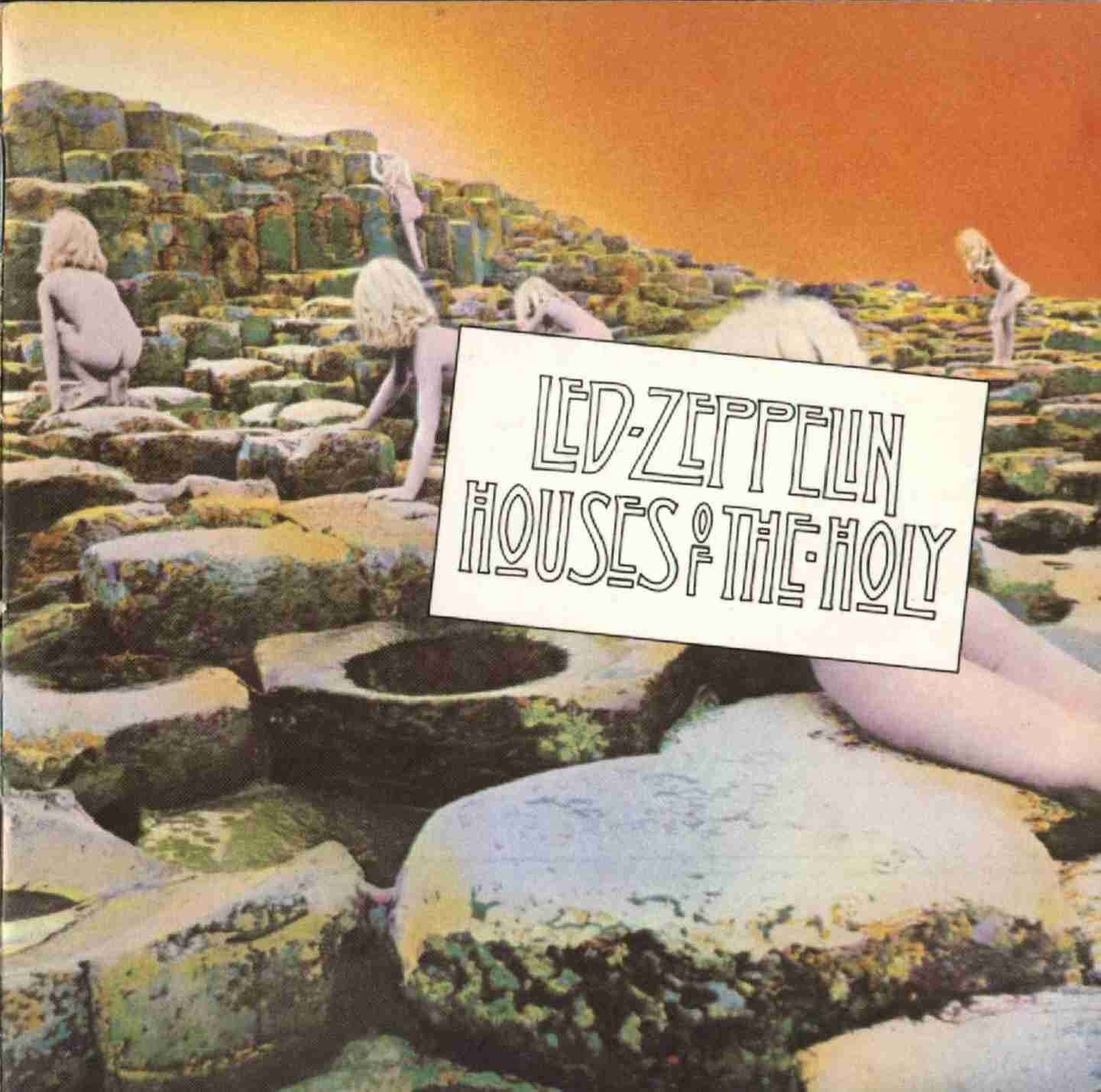

Led Zeppelin

'No Quarter'

Perhaps it is simply the familiar droning of John Paul Jones’ Fender Rhodes, but Led Zeppelin’s “No Quarter” had much the same effect on me as “Blue Jay Way” growing up.

Taken from their 1973 album, Houses of the Holy, the record’s cover was uncharacteristically nightmarish. Following on from the relatively tame covers of Led Zeppelin’s first four self-titled albums, Hipgnosis’ cover for their fifth effort seemed to signify a break in the mood of the moment, tapping into an oddly Freudian melancholy that had begun to hang over the 1970s.

The cover was apparently inspired by Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 novel Childhood’s End, in which humanity enters a golden era of prosperity after sacrificing all autonomy to an omniscient alien race of Overlords. Looking backwards from that moment, this seems to be a comment on the long shadow of Mutually Assured Destruction that outlived World War II. Looking ahead, it seems to foreshadow the insidious reality of now and the depressive hedonia of a then-nascent neoliberalism.

Whilst the album itself is a diverse affair, “No Quarter” seems to carry over the anxiety of isolation captured by George Harrion back in 1967. With its familiar lyrics of disturbed interiority — “Close the door, put out the light / You know they won’t be home tonight” — the song seems to cower under the threat of a mysterious and merciless ‘they’. However, despite its fearful sentiment, it is a propulsive track, once again sonically pushing through its own skin.

Already a favourite on the inherited turntable back home, I most vividly remember listening to the song on one particular occasion.

I was sitting with my Dad in his car, watching as the headlights cast strange shadows through the woods on the edge of the Humber Bridge Country Park, on a cold October night in the late 1990s. Hallowe’en was in the air but we were there to catch a bus into town to partake in another autumnal tradition: Hull Fair, Europe’s largest and oldest travelling fair.

Listening to “No Quarter” that night felt like a ritual or an invocation. We let the song play out and then, once it was over, we crossed over the threshold into another world.

The fair had an irresistible pull for someone my age. It was a long weekend of rollercoasters, sugar, music, representing a certain social outsideness. It was essentially a rave, captured in a car park and given a permit. However, having only been born in 1991, this was the closest I got to experiencing the otherworldly euphoria of ‘90s dance culture. By the time I was culturally lucid enough to pay it any attention, it was over. Nevertheless, the sound palette was unforgettable.

Weaving our way between waltzers and hook-a-ducks, down the less crowded alleyways that separated this Temporary Autonomous Zone from the city outside, I will never forget the sheer force of what I later learned was called drum’n’bass. The genre’s titular components were visceral, rearranging your organs that were already under strain from the copious amounts of refined sugar being fed into them. I remember walking this path, sound blaring to our left, emanating from Terminator-themed roller coasters along with Doppler screams, and the pregnant stillness of caravans to our right, inside which were palm readers and fortunes tellers and the temporary homes of the travellers who ran the rides.

Years later, learning about the popular history of drum’n’bass, jungle, and gabba, discovering that this confluence of genres did not make up a subculture exclusive to the traveller community was something I found culturally disorientating. Nevertheless, I felt a kinship with it. The deep pleasure of listening to “No Quarter” in that autumnal car park provided a fruitful context to hear these new sounds within. My ears became attuned to the funereal atmosphere that lurked underneath, produced by synths and drones and other unidentifiable sonic objects. It was “Blue Jay Way” and “No Quarter” but for now. It was a vector on which other worlds and emotional landscapes were travelling. It was the Darkside.

D-Cruze

'Lonely'

The push and pull that exists between these sorts of songs, with their almost liturgical grandeur that nonetheless channels the most introspective of emotional experiences, is something I continue to gravitate towards today. D’Cruze’s “Lonely”, released on Suburban Base Records in 1994, may be the most explicit example of this same vibe, as produced by the E Generation.

This was the ingenuity of so-called Darkside Jungle: turning existential angst into fuel for the dance. The personal is made impersonal, the depressive euphoric, and vice versa. Origin Unknown’s 1993 twelve-inch, “Valley of the Shadows”, sampling the dreamscapes of Delia Derbyshire and Barry Bermange’s oneiric radio inventions, is arguably the classic example of the ways in which junglists were sensually transforming the life of the mind into an infectious body boogie, but it is D’Cruze, on this single most perfectly, who captures the sonic transportation and bittersweet contradictions of rave culture most affectingly for me.

Sampling a vocal motif from Regina Belle’s late ‘80s R&B number, “Good Lovin’”, “Lonely” hovers between existences, between bedroom production and rave function. The soulful refrain of the loved-up original — “I could never, never be lonely” — becomes as melancholic as it is hopeful; as self-comforting as it is defiant. Here, the egress afforded to the bedroom producer is made plastic in more ways than one. Vinyl is pressed as easily as the world outside is transformed. Skittering breakbeats dismantle walls and egos, dragging the producer out and the raver in. In and out, in and out, from bedroom to radio to club and back again.

It reminds me of something David Toop once wrote about Aphex Twin: “Surfing on sine waves, he would lead a pack of young boffins out of the computer screen glow of their bedrooms into the public domain of clubs, shops and charts, then back in and out of more bedrooms in a feedback loop of infinite dimensions.” This isn’t just true of AFX — this is the effect of jungle’s anarchitecture. Its frequencies reflect and then distort reality, tracking body and soul through a network of wormholes. The under-acknowledged anxiety of the counterculture becomes the lifeblood of a new subculture that is both seeking an exit from the drudgery of the everyday whilst nonetheless retaining a perspective on the things that rave is running away from. It is a dub mutation, turning a world of echo into a prison of mirrors, and it’s looked sick ever since they installed the lasers in there.

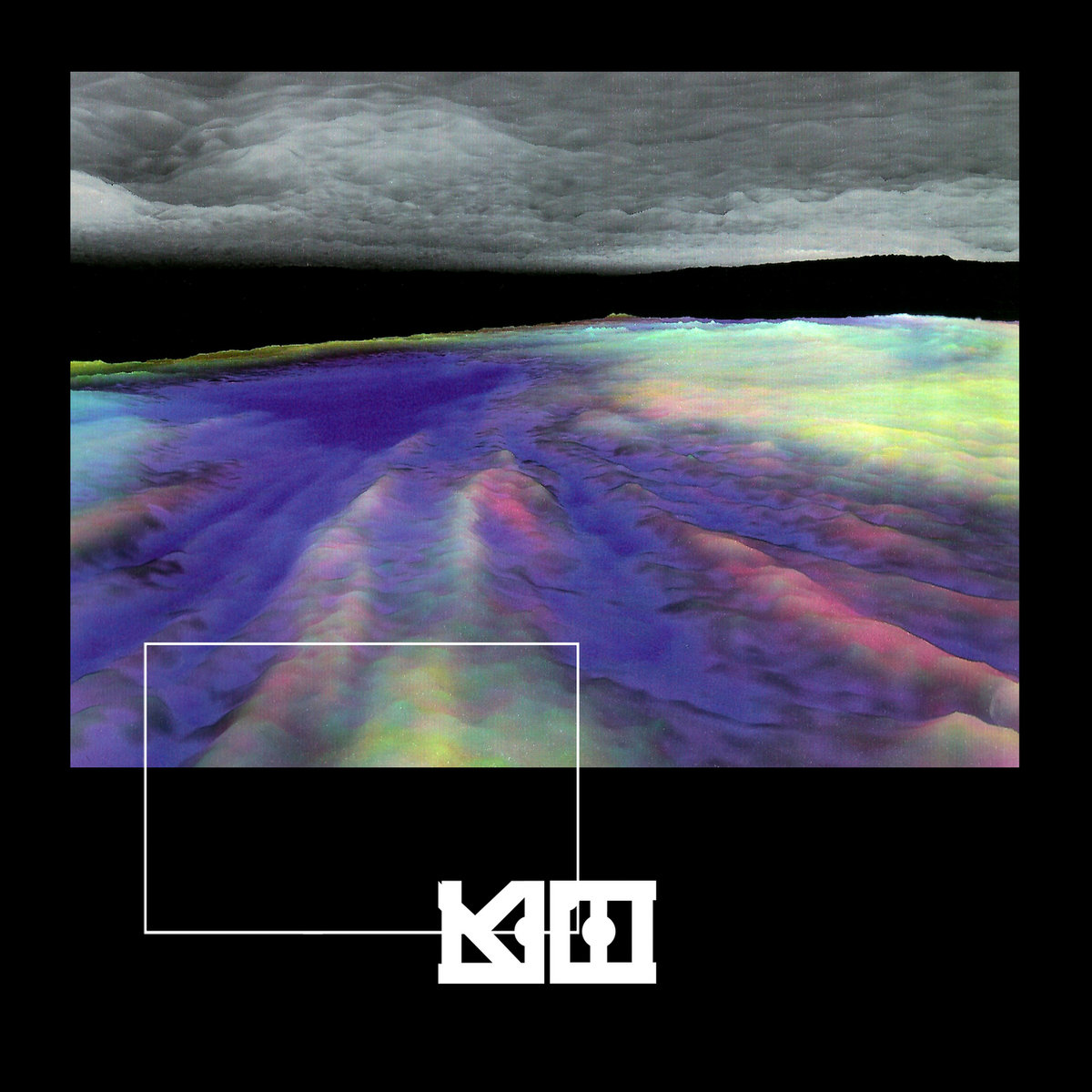

Lee Gamble

'Oneiric Contur'

Years later, in my directionless early 20s, stranded in Hull and living under arduous circumstances at home, I would drive out to the Humber Bridge Country Park almost every night of the week, with a book, a pack of cigarettes, and an enormous zip folder of CD-Rs.

One foggy night in 2014, having recently acquired Lee Gamble’s album KOCH, I put it in the CD player and slowly drove away. I remember I wasn’t ready to go home yet, I wanted to hear more of this record, so I drove out to the Saltend Chemical Park on the other side of the city and listened to the rest of the album under the twinkling lights of the oil refinery.

The sound system in my Mum’s old car wasn’t very good. The album’s more subdued moments would get lost at times, melting into the sounds of the car and the bad weather outside. It was anxiety-inducing, in all honesty, but I liked it.

Listening to KOCH, I felt like I was listening to the atmospherics of darkside, left to echo and percolate and reverberate around themselves. It was sound extracted from the prison of mirrors, dug up like a time capsule, and inside all you find is decomposing sludge. (That’s a compliment, I promise.)

What are dreams if not precisely this? Deprived of the stimulation of unfolding experience, the unconscious mind feeds back onto itself. At the start of the twenty-first century it felt like our collective unconscious was going through a similar process, as our dreams of the future no longer look like dreams awake, but regurgitations at the end of history. In more recent decades, this experience has torn through dance culture like a virus. The terms used to describe this virus quickly become journalistic cliche or intellectual cul-de-sac but the sensation remains.

This sensation, whatever we want to call it — this “jangling of the nerves” — finds itself compressed into ever tighter kernels. The wistful organ on “Blue Jay Way” is still here, in spirit, but it has been compressed, broken down, its particles accelerated. What might emerge when they collide anew? I think Fisher, after Fredric Jameson, would call them “baroque sunbursts” — when “rays from another world suddenly break into this one, we are reminded that Utopia exists and that other systems, other spaces are still possible.”

Nazar

'Retaliation'

This past week, I’ve been listening to a lot of new music as well. There’s not a lot else to do. Thankfully, much of it is providing respite from the oppressive nature of quarantine. Although there are few opportunities for escape, there are plenty of opportunities for the imagination to run wild, picturing a world beyond the threshold of present circumstances.

Nazar’s recently released album, Guerrilla, in particular, feels like a “baroque sunburst”, bursting forth from now. But baroque how? “The Baroque refers not to an essence but rather to an operative function, to a trait,” writes Gilles Deleuze. “It endlessly produces folds.” The baroque is psychedelic before the fact, and remains psychedelic after it too.

Born in Angola but living in Belgium until after the end of the country’s 27-year civil war, Guerrilla deals with Nazar’s experiences, as well as his family’s experiences, of Angola’s fraught recent history, folding a life and a conflict into just 45 minutes of “Rough Kuduro”.

How does music contend with a war and its effect on both family and nation? How do you describe music like this in words? The context provides us with a period of time in which to situate it but it is hardly an archival document. According to its press release, the album takes the very make-up of not just Nazar’s life but of an entire community and “weaponises” it. What kind of weapon is created?

To “weaponise” something suggests adapting its function. So, what is the function of Guerrilla? Its essence is, undoubtedly, war and family trauma, but its function is dance, of a sort. This doesn’t trivialise its subject matter but puts it explicitly to work, actualising a world post-conflict. It opens up a space for itself to exist in, beyond the borders of the contested nation and the broken family at its heart. It is sensual, embodied, even violent. It is historical, but it is also speculative. It documents and ruptures. It is a hyperstition. It is an “afro hauntology”. It is also a psychedelia for now, pushing through the scar tissue of the recent past to forge new futures. It is haunted, perhaps, but undefeated.

We need more music like it in times like these. Thankfully, there is plenty of it out there. “Stay in bed, float upstream”, was what the Beatles recommended. We remain capable of this same passivity, but it is a productive passivity. You can do it on your feet or lying down, at home or in the club. All you have to do is affirm the function of the music that you listen to and the foldings it endlessly produces. Let it work on you. You might find it takes you to another world.

Matt Colquhoun

Matt Colquhoun is a writer and photographer from Hull, East Yorkshire. He currently lives in London and writes at xenogothic.com. In “Looking for an Exit: Sonic Coordinates for Egress“, Matt Colquhoun considers the function of psychedelia in the unfinished work of the late Mark Fisher, through a quarantine playlist that wonders how to not just imagine other worlds but bringing them into being.

Matt’s book Egress: On Mourning, Melancholy and Mark Fisher, was recently published by Repeater Books:

‘Egress is the first book to consider the legacy and work of the writer, cultural critic and cult academic Mark Fisher. Narrated in orbit of his death as experienced by a community of friends and students in 2017, it analyses Fisher’s philosophical trajectory, from his days as a PhD student at the University of Warwick to the development of his unfinished book on Acid Communism. Taking the word “egress” as its starting point — a word used by Fisher in his book The Weird and the Eerie to describe an escape from present circumstances as experienced by the characters in countless examples of weird fiction — Egress considers the politics of death and community in a way that is indebted to Fisher’s own forms of cultural criticism, ruminating on personal experience in the hope of making it productively impersonal.’

Mark Fisher

(1968–2017)

Mark Fisher was a writer, political activist, lecturer and a culture theorist who vividly chronicled the early days of the digital revolution. In a courtyard at Goldsmiths College, the south-east London university in which Fisher lectured as part of the Department of Visual Cultures faculty, a mural recalling his call to arms reads: “Emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a natural order . . . just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable.” Along with such posts as “Spinoza’s The Ethics is like running Videodrome [the David Cronenberg film] on cassette” the mural typifies his engaging, intelligent, sensitive and funny output that spans music, film, literature, politics, football and more. As friend and ex-colleague, Simon O’Sullivan (Head of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths) notes in his tribute to Fisher, ‘it was Mark’s ability to communicate sometimes complex ideas with such apparent ease and with purchase on our contemporary moment, that gave him a readership well beyond the Academy.’ With roots in the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) – a rouge, student-led cultural theorist collective in Warwick University’s philosophy department in the mid-1990s who, ‘went on to become one the most mythologised groups in recent British intellectual history’ – Fisher rose to prominence with his K-Punk blog (now archived), which launched in 2003.